11

Dec

Exclusive

Peak Anatomy: Why MVPs are at their best at 27

Highlights

Why 27 is the golden age for basketball MVPs, according to data, science and experience.

- Age 27 often marks a player’s peak performance window.

- Childhood learning and diversified sport backgrounds drive skill mastery.

- Tactical skills develop through repetition and shared game experience.

- The right level of challenge is crucial for ongoing growth.

- Evolving sports science is reshaping peak age and longevity.

Golden State Warriors guard and the greatest shooter of all-time Stephen Curry made history in 2016, winning his second consecutive NBA Most Valuable Player award by unanimous vote.

It followed his 2015 NBA championship and his 2015–16 NBA scoring and steals titles.

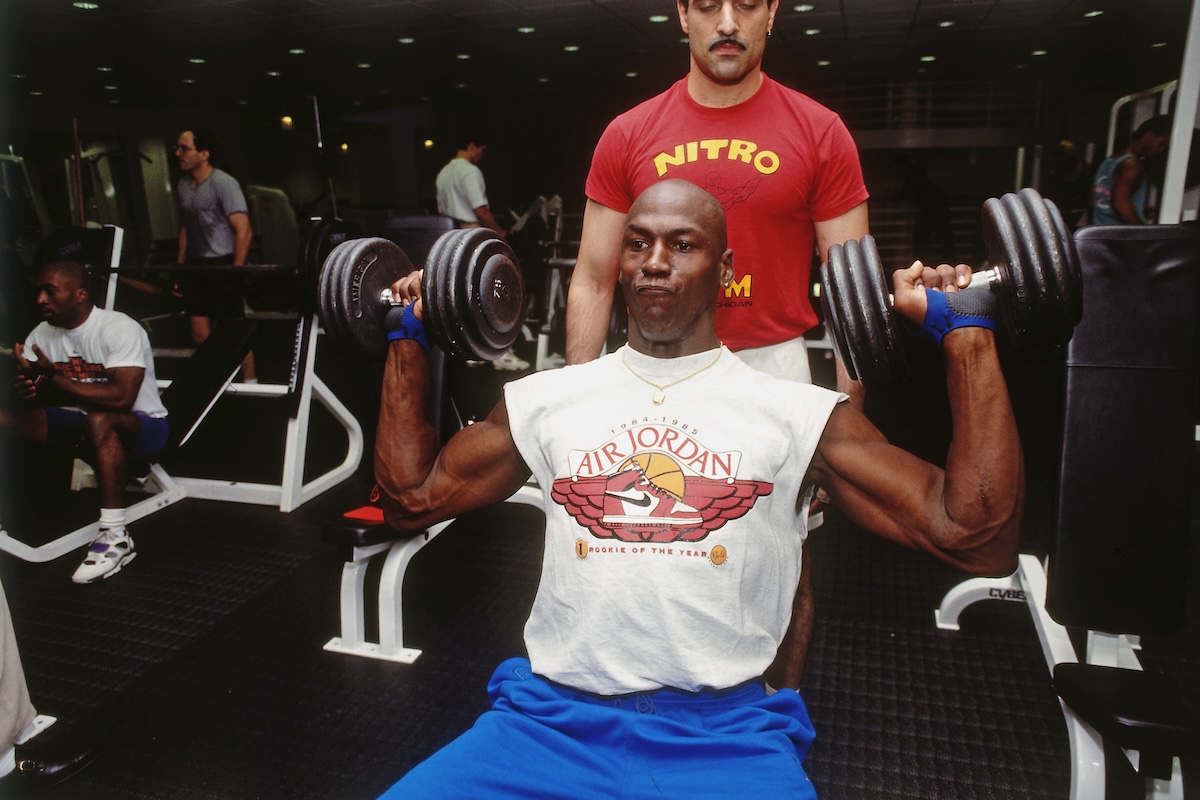

The GOAT Michael Jordan had one of his most efficient seasons ever in 1990-91, winning his first NBA championship, second MVP Award and Finals MVP.

Similarly, LeBron James had one of his most statistically efficient and successful years during the 2012-13 season. Like Jordan, he won both regular season MVP and Finals MVP and the NBA championship.

And in Australia in 2020, now Adelaide 36ers’ superstar Bryce Cotton won the Andrew Gaze Trophy as the NBL Most Valuable Player for the Perth Wildcats. The second of five for Cotton. Andrew Gaze himself, won his second MVP in 1992.

Curry, Jordan, James, Cotton and Gaze were all 27 years old.

As were Bill Russell, Earvin “Magic” Johnson, Shaquille O’Neal, Kevin Garnett, Larry Bird, Moses Malone and 2023 NBL MVP Xavier Cooks.

WNBA star A'ja Wilson won her third WNBA MVP at 27, turning 28 late in the season, in 2024 and Jonquel Jones her first in 2021. Surprisingly, Australia’s greatest ever basketball player Lauren Jackson didn’t win a WNBA MVP at 27, she did at 26 and 29 after winning her first at 22!

Across various sports, athletes “peak” at different ages. Where Olympic level swimmers are on average 23-years-old, every Australian Eventing rider in the 2024 Paris Olympics was over 40. The most efficient NASCAR drivers are aged 39. And in basketball, NBA MVPs are predominantly 27 or 28.

Historically, the average NBA MVP age sits just over 27, and the most common age is 28 – late 20s is clearly the sweet spot. There are, of course, outliers at either end of the age spectrum. Chicago star Derrick Rose was 22 in 2011 and Wes Unseld 22 in 1969 while Utah Jazz Hall of Famer Karl Malone is the oldest at 35 in 1999.

While a player’s peak is subjective, various metrics such as player efficiency rating (PER), box plus-minus (BPM), and win shares (WS) can be used to measure a player’s performance.

So, why are the majority of NBA MVPs aged between 27 and 30?

What goes into becoming a professional basketball player? What skills are required? What level of mental resilience?

It's science as these experts explain.

Implicit Learning

Learning any kind of skill young is beneficial. Generally speaking, learning as a child is easier. Swimming, riding a bike, dribbling a ball. Adults have a tendency to over-analyse, whereas a child’s brain is always “hungry for learning”, explained Tina Van Duijin.

Van Duijin is a researcher and lecturer in Skill Acquisition and Motor Control at the University of Otago in New Zealand. She is interested in how people perform and multitask under stress, and her previous research has focused on improving motor skill learning and performance.

“We control movements all the time. Some of our movements we are aware of and we can control consciously and a lot of movements we don’t control consciously. We just do them”, said Van Duijin.

“As we progress, as we practice and become more fluent in our movement, we're also starting to become more economic physically. We use less energy to do the same movement. We're obviously becoming more precise, and we're also becoming more automated in terms of conscious control.”

Put simply, when a skill becomes implicit, you have a wider bandwidth for implementing other, more complicated skills. Think spins, crossovers, jump hooks, anticipating your opponents moves. So as far as development goes, early mornings and endless drills are essential.

“I had amazing experiences from quite a young age,” former professional and Australian Opals Olympic basketball player Shelley Gorman said.

“I went to my first Olympics when I was 19, so I was exposed to a lot of basketball and a lot of experience when I was younger. Some players don't make it until they're a bit older.”

By and large, most high-level basketball players begin playing as kids. However, exceptions always exist. One such outlier is Indiana Pacers’ Pascal Siakam. Siakam was 17 before he even considered a career in professional basketball. Five years later he was awarded NBA G-League MVP.

Legendary former power forward Tim Duncan had a similar career trajectory. He began his sporting career as a competitive swimmer before moving into basketball after Hurricane Hugo destroyed his only local Olympic sized swimming pool when he was 14. After an incredibly successful 19-year basketball career, Duncan was inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame alongside Kobe Bryant and Kevin Garnett in 2020.

Although older, both Siakam and Duncan played other sports, something Sports Specialist William Sheehan says is beneficial for both skill development and career longevity.

Early Specialisation Versus Diversifying

Most Olympic pools will be filled with elite swimmers aged 14 to 25, an article published by SwimSwam reveals.

“Swimming, for example, generally starts from a very young age and is often the sole focus for that individual throughout their childhood. That's what we call early specialisation, where an individual focuses on a particular sport or activity for the majority of the time,” Sheehan explained.

“Whereas you look at team sports, players tend to experience more sports at a younger age, so they diversify more. So rather than solely playing basketball year round, they've probably been exposed to soccer or baseball or other sports outside of their own.

“And through doing that, they often develop skills that are transferable. So some of the skills they develop playing soccer or softball through hand-eye coordination or agility can transfer through to their performance in basketball,” he said.

“There's also research to show that those who specialise in a sport from an early age tend to get injured more often. That's often why they have shorter careers, and because they invest so much time in only one sport early on is probably why they reach their peak performance earlier on.”

Regardless of whether an athlete is playing competitive soccer, basketball, or something else entirely, practice should be intentional and purposeful, Sheehan explained.

“You might have heard of the 10,000 hour rule where the more time you spend focusing or practising a task, the better you get,” he said.

“That research was based on 10,000 hours of intentional practice. So practice had a particular focus and players had clear goals.

“You probably know someone who has been doing an activity or an instrument or a sport for their whole lives and has probably accumulated more than 10,000 hours of practice, but they're still just as mediocre as ever. And it's probably because a lot of their practice hasn't been purposeful or directed in the right way.”

Developing Tactical Skills

Sheehan is a researcher and lecturer in the School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation at the University of Technology in Sydney, having worked previously as a Sports Scientist for the Sydney Swans and GWS Giants in the AFL. Sheehan’s role involved analysing AFL gameplay and researching how specific physical, technical, and tactical skills influence a player’s success.

“There are two ways we looked at measuring tactical performance or cooperative behaviour between players. The first was using what's called social network analysis,” said Sheehan.

“So we were quantifying the number and quality of passing interactions between players, and we were able to see which players interact with certain players more or when certain passing interactions occur, maybe more so than others. This tended to be the outcome in the game. So we were able to identify influential players within our own social network and also other key players and other teams' social networks.

“The theory being if you could essentially nullify those key influences, you would ultimately disrupt their ability to compete and play to their best ability,” he said.

Those complex skills we mentioned earlier. They go far beyond perfecting a Euro-step.

“When we think about tactical behaviour, it generally develops over time through mutual experiences,” said Sheehan.

“So if you think about a more senior team who have older players who have been playing and practising together for a really long period of time, they have probably become really good at picking up on cues and being able to adjust their positions to be able to work.

“The more time you can spend practising and playing together, the more attuned you become to those players and how they tend to act, and you can adjust accordingly.

“This develops over time intrinsically, just through continual exposure,” he said.

Although Sheehan’s research primarily analysed AFL gameplay, his findings are synonymous with Gorman’s experiences.

“You’re forever working on your skills, your shooting, your ball handling,” she said.

“Different coaches have different ideas. That was one of the good things about playing overseas. You have different coaches. They've got different ideas and so you're always learning. Because they do things differently. They might run systems differently. The smallest thing might be able to help you or change your perspective or change the way you see things.

“What's happening today is a lot of players are playing a lot of basketball. Which is great. And you learn from just being out on the floor. But I think what a lot of players need to do is work on their skill.

“They don't do enough work outside of team training.”

Coaching Skill Development

These days, most high-level coaching plans are underpinned by a wealth of sports science. Dr. Job Fransen is a senior lecturer at Charles Sturt University specialising in skill acquisition and motor expertise. He has worked with several major sporting franchises, including reigning 2024-25 NBA champions Oklahoma City Thunder, Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), Sydney Swans Football Club, Rugby Australia and more.

To avoid plateauing, players need to be in a constant state of “optimal learning”, explained Dr. Fransen.

“We all know a learning curve where you kind of develop really quickly in the beginning, learn a task, and then gradually over time that learning curve plateaus off and then it becomes entirely flat or it decreases over time,” he said.

“The reason why that happens is when you engage in skill learning, when you do it early, you make lots of mistakes. And because you make lots of mistakes and all the mistakes themselves are of large magnitude, every time you overcome one of those mistakes, you get a large jump in performance as a result. And of course, as you get better, the mistakes you make are less frequent and they are also less large.”

Dr. Fransen said, while players need to be challenged, they also need to be challenged at the right point in time.

“What often happens in performance organisations is you have a good player who performs well,” he said.

“As a result, every learning environment you put them in becomes increasingly less challenging. Because you can only play basketball with other people, you are constantly challenged less by those other people and therefore your performance curve stagnates.

“So one of the, let's call it, secrets or strategies or tricks to ensure players continue to develop is to optimally challenge them.”

“Now, of course, there are also aspects of physical fitness,” he said. “The reason why you don't often see 34 and 35 year old players who are still in that really fast accelerated development is because to put them in these conditions of really high skill challenge, you also often have to physically challenge them quite significantly.

“Take for example, a player who's doing really well, they're 18, they're 7-foot or 7-foot-1, like really tall. But they’re limited in movement capabilities, physical fitness and some of the skilfulness to really thrive in these challenging environments.

“If you put them with four other players who are more skilled, fitter, move better than them, they're constantly being over challenged in those practice sessions. And when you're being over challenged, your skill learning curve also plateaus. So you really have to constantly try to find that optimal challenge point.”

Enter intrinsic motivation

“If a player can't constantly challenge themselves at an optimal level, they're not really going to get there,” Dr. Fransen said.

"A player has to be intrinsically motivated to consistently practice at a difficulty level that's optimal for them. It means in the Goldilocks zone, not too difficult and not too easy.

“The difficulty is, as your skill level develops, you also have to dynamically adjust the challenge of your practice. And most players can't do that because they're not properly supported.

“Imagine you're the best player in a league. The MVP. What kind of environments can you still create to optimally challenge that player? It's really difficult to do.

“Too often we end up in a level of comfort where we go, ‘I'll just repeat the training I did last Thursday.’ You're basically kind of saying, ‘Look, we're happy with plateauing here. We don't need to develop any further.’”

When reflecting on her own experiences, Gorman said she has always been internally driven. In all areas of her life.

“I wanted to do the work, and I think that's why I got where I did,” Gorman said.

“That's why I achieved what I did.

“I'm not a great athlete. I’m not naturally super quick. I can't jump.I don’t have any of those really natural athletic skills. I just did a lot of work.”

Changes in Sports Science and Career Longevity

Improvements in sports science means players are dominating earlier and playing longer.

OKC Thunder won last season’s NBA Championship with an average player age of 25.6. And Milwaukee Bucks’ Giannis Antetokounmpo earned his “Greek Freak” nickname long before he was 27.

All while 40-year-old LeBron James heads into his 23rd NBA season as capable as ever.

Gorman, now 56, retired more than 20 years ago, and said professional basketball looks different now.

“Everything's better. Everything is more advanced than when I played,” she said.

Typically, after peaking about age 27, most high-level basketball players begin regressing after their 31st birthday. But that age is starting to stretch given sports science.

Gorman retired from professional basketball at 32.

“Physically my body was starting to break down,” said Gorman.

“I wasn't as sharp, obviously physically, but also mentally. So I started to lose a bit of confidence and I was just frustrated.

“I knew I was ready. And I had kind of done everything I wanted to do,” she said.

As more money and resources are injected into improving coaching and career longevity across all sports, fans can expect a more dynamic and age diverse playing field.

For basketballers, ages 27 to 29, are still prime as all the variables to be truly world class merge into a single time frame: talent; motor learning; skill development; maturity; desire; understanding; and physical peak.

It’s why the greatest players of all-time had their greatest years before turning 30.

Exclusive Newsletter

Aussies in your Inbox: Don't miss a point, assist rebound or steal by Aussies competing overseas. Sign-up now!